On Not Missing Ariel Pink or John Maus Even Slightly

Of all the curious outcomes of the January 6 insurrection, one of the more encouraging ones would seem to be the substantial reduction of the music-world prominence of Ariel Pink and John Maus. Pink and Maus thought it would be cool to attend the January 6 riot at the Capitol, though Pink asserted that he was there merely to peacefully support Trump.

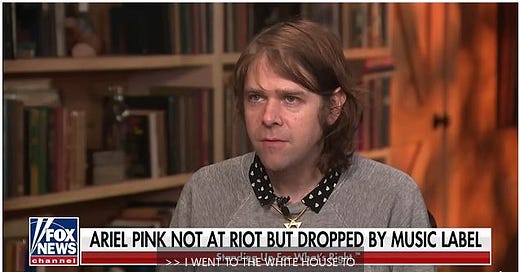

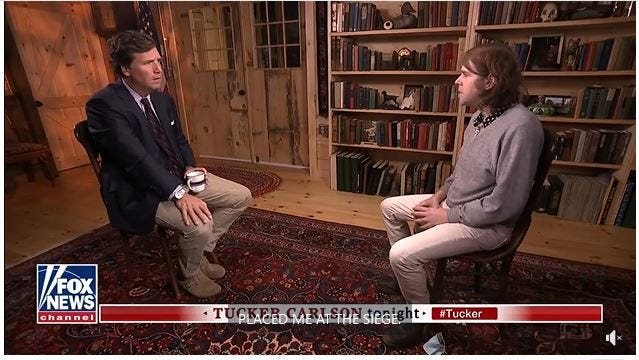

But neither of those storylines — neither the one involving a direct attack on American democracy nor the one involving merely supporting a grossly corrupt, racist, misogynist, neo-fascist asshole in his attempt to negate American democracy — turned out to be real palatable in the relatively liberal world of arty indie rock that had previously been the base for both musicians. Pink was dropped by his label, Mexican Summer, and he described his own career as “destroyed” by what he called being “punished.” (As opposed to, say, by having such terrible judgment that he made himself wildly unmarketable.) He went on the show of white-supremacy-rhetoric-spewing idiot Tucker Carlson and complained that “people are so mean,” a move that he later acknowledged actually “didn’t improve things.” Ya think?

Maus is also being met with skepticism, despite having played his cards with a little better judgment in the wake of the riot. He was recently dropped from a headlining spot at ElectroniCON 2023 after concerns were raised about his contributions to a controversial, alt-right-affiliated and since-cancelled Adult Swim show called Million Dollar Extreme Presents: World Peace. The scrutiny on that connection, it seems fair to say, was more intense because of Maus’ appearance at the insurrection.

Nearly three years after January 6, Ariel Pink is still generating music, in some fashion, but if you search for reviews of the releases you will come up with basically nothing. There is no glowing Pitchfork writeup, no quick take on Pigeons and Planes. Maus did not perform in the U.S. for roughly two years after the insurrection, according to Pitchfork, though he appears to have done some recent gigs both domestically and in Europe. It appears that his shtick is still to shout into a Grand Canyon-sized pool of reverb about vague themes and flail around on stage in an Oxford shirt: ya gotta play the hits, after all.

From my point of view, the outcome is more than fair politically. What happened to Pink is not remotely “mean.” Mean, in the world of actual politics, is what is happening in Gaza. Mean is throwing a woman in prison for two years for helping her daughter have an abortion thanks to legal changes ushered in via Trump. Ariel Pink is not experiencing the slightest hint of that actual, real-world political meanness, in spite of having taken a field trip to the most serious attack on American democracy since the Civil War. He’s merely having to grapple with the drab, workaday reality that everybody else endures who is not fawned over for playing 4-chord guitar tunes.

But more than just being political just-desserts, the decline of the Pink/Maus regime validates my sense that the aesthetics of these performers, which the music press seemed to admire so much once upon a time, were actually bankrupt from the get-go. Music, after all, is not just a bottomless, self-referential collection of sonic quirks and stylistic quotations and knowing references to vintage gear, even if all that aesthetic gymnastics is a lot of what makes it marketable to young people and advertisers. The sound and the culture of independent music is not simply an inert medium, like a tube of paint, that should be equally exploitable by any random fascist who think it’s witty to dabble in the genre. Not that there isn’t room for a diversity of perspectives: of course there is. But at the end of the day, musicians that purport to invoke a sound and a community that has traditionally given support to marginality also ought to in fact have some concern about about the lives of the marginal, or at least not be actively, outspokenly allied with political movements that seek to oppress and to denigrate.

Neither Pink nor Maus, as far as I could tell, ever believed that any connection ought to exist between the sonic poses of their music and the struggles of the real world, never gave any indication that, beneath the meticulous sound design and the “indie” posturing, there was any actual empathy for others. In fact, to the extent that they spoke on real-world politics, these guys were always the ones expressing contempt for “political correctness” — see, e.g., Pink’s criticism of gay marriage, his expression of sympathy for the deeply bigoted Westboro Baptist church, and so on — and/or (in Maus’ case) issuing some impenetrable “academic” rationalization (sometimes to apologize precisely for what an idiot Pink is) that, like some sort of indie Jordan Peterson mumbling over a DX7 pad, rendered it utterly impossible to know what the man actually believes (but was always notably open to being interpreted as sympathetic to the hard right). This is why the sound of both these guys is so hyper-ironic in its tone, why Maus’ vocals are invariably buried in a murky sea of reverb: because the entire thing is an affectation and a put-on by a pair of guys who would be booed off the stage (except perhaps in the world of country music) if they found the courage to just state their actual views plainly.

On January 6, the ironic mask came off. These guys made their real-world allegiances clear. There may be some small segment of the music-consuming public that still finds it compelling to hear what tongue-in-cheek nonsense Pink and Maus can blather over some carefully curated “indie”-flavored sounds, folks who still think it’s hip and edgy to be in on the “joke” that is the Pink/Maus model of deep insincerity and reactionary politics. But in general that ship has sailed.